Cayenne, 13 June 2018

54 rue Madame Payé in the centre of Cayenne, is an annex to the Musée des Cultures Guyanaises at No 78. No 54 has been restored using traditional Creole building techniques and local materials. What is most significant is that the last owner of the original house was Herménégilde Tell. Tell’s personal biography is closely woven into the story of the Penal Administration and its closure but he is also a key figure in the wider political history of French Guiana. Although most, if not all, traces of the bagne have long vanished from Cayenne which only continues to function as metonym for the penal colony in Metropolitan France, the bagne functions as a shadowy presence felt as much through its absence as tangible heritage and also as a thread running through personal and local histories such as that of Herménégilde Tell.

Born in 1868, Herménégilde Philippe Hippolyte Athénodore Tell was the son of a former slave (his father was just ten years old when slavery was abolished in 1848 and already working on a plantation in Cayenne) and went on to become the Director of the A.P. at Saint Laurent du Maroni. Tell’s position as Director of the A.P. lies at the nexus of the complex racial pathologies of France’s colonial project. On the one hand, Tell represents the opportunities for the local population presented by the arrival of the penal colony which began operation in French Guiana a few years after the abolition of slavery. His father was also employed by the A.P. as a tonnelier [cooper]. Tell began work as a guard at the age of 17 and rose through the ranks to the level of Director in 1919. His career trajectory thus runs counter to a more widely known narrative which focuses on the employment of military personnel from France and its other colonies to work on a temporary basis in the bagne before being assigned elsewhere. Yet, recent discourse around the bagne and its legacy point to Tell’s unusual position as someone who successfully rose through the ranks as one of the keys to understanding the decarceration process. Ironically, it was the image of the son of a slave overseeing the punishment of a predominantly white convict population, as reported by Albert Londres, that is sometimes proposed as precipitating the public outcry about the bagne and the call, from mainland France, for its closure. Where the public either ignored or denied its existence previously or harboured a fascination for its myths, exoticism and cruelty, Londres’ reports brought a previously blurred fantasy into sharp relief not least with his critique of Tell’s inept management of the A.P. This critique was posited alongside the devastating accounts of the liberated convicts forced to do ‘doublage’ in the colony – the image of abject white poverty juxtaposed against the upward social and political mobility of the Creole population.

An awareness of Tell’s position in all this is useful in understanding the racist underpinnings that contributed towards the closure of the bagne. It also acts as a reminder of the complexity of decarceration and the complex, local and global stakes of such processes. At the same time, this discourse, more prominent in French Guiana perhaps, should also be subject to scrutiny.

When I visited 54 rue Madame Payé last year, the story of Tell’s rise and fall in the A.P. featured on panels in the downstairs of the house, cited Albert Londres’ Au Bagne suggesting that the initial reporting emphasized Tell’s racial identity in a brief clause that was later removed in subsequent republications.

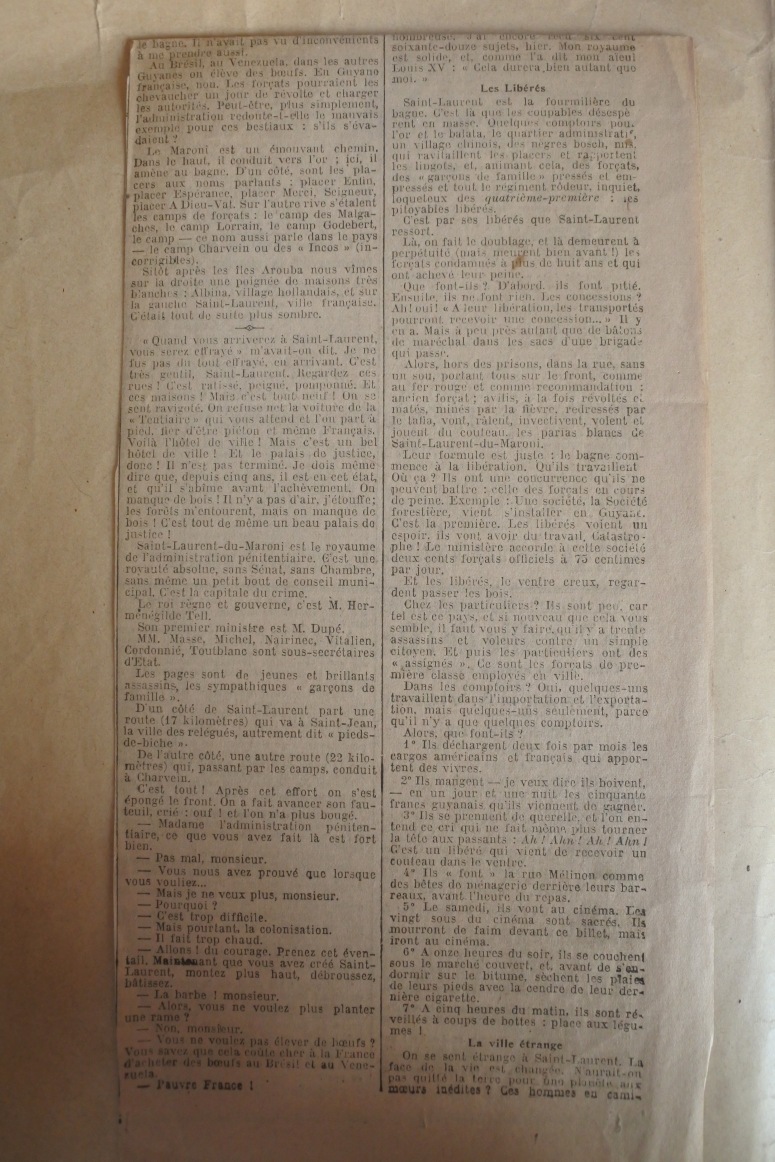

‘Saint Laurent-du-Maroni…c’est la capitale du crime. Le roi règne et gouverne, c’est M. Herménégilde Tell, un nègre…’ (Albert Londres, Au Bagne, 1923)

A few months later I was looking for the quotation in the book-version of Londres’ reports and found that the clause was still there. It hadn’t been edited out later or perhaps has been returned in later editions. Consequently, I went back to the original reports I had documented on a visit to ANOM in 2015. As it turned out, the clause was missing from the original reports in Le Petit Parisien and had been reinserted in later editions, no doubt based on Londres’ original manuscript.

‘Saint Laurent-du-Maroni est le royaume de l’administration pénitentiaire. C’est une royauté absolu, sans Sénat, sans Chambre, sans même un petit bout de conseil municipal. C’est la capitale du crime.

Le roi règne et gouverne, c’est M. Herménégilde Tell.’

What this suggests is that despite Londres’ explicit slur, this was actually censored or edited out by the editors at Le Petit Parisien in its initial publication. Why? The museum panel that referred inaccurately to a later censorship suggested that:

‘Ce dernier terme « un nègre », n’apparaît plus dans les éditions suivantes, probablement pour sa connotation raciste ou trop évocatrice de l’esclavage… Mais c’est effectivement le fils d’un ancien esclave qui est devenu directeur de l’administration pénitentiaire, après en avoir gravi les échelons.’

Cutting the reference did not perhaps remove all implication of Tell’s race and background but instead allowed these to operate on public imagination without being more forcibly and crudely articulated. Moreover, it is interesting to note that this minor error has now disappeared from the museum’s presentation of tell. This is not so much a case of the error having been corrected at 54 rue Madame Payé but the panels have been changed since my last visit. In general the text on the panels has been reduced, summarized perhaps to make room for the new exhibition on postcards upstairs. The relationship between Londres and Tell is still highlighted complete with moody photo of Londres. Here, however, Londres’ exact reference to Tell that was previously cited has been omitted. Instead he is simply described as having ‘skewered’ [épinglé] Tell.

‘La fin de ce parcours est ternie, dans le sillage de l’enquête d’Albert LONDRES au bagne. Sa personne [Tell] et sa fonction sont directement épinglées par le reporter. Le Gouverneur CHANEL, arrive en Guyane le 17 novembre 1923, met en doute son intégrité et demande sans relâche sa mise à la retraite, estimant que « son maintien à la tête de l’AP serait un obstacle certain à l’œuvre de réforme entreprise ».’

Both the earlier panels and the new version describe Tell as receiving commendation for his work but having come under varying degrees of criticism for his personality throughout his career in the A.P. While I’ve heard people describe the devastating effect Londres’ personal campaign against Tell had on him (he died 6 years later in 1931), there is a need to be wary of identifying him as scapegoat for the failure of the bagne. No doubt his high profile in French Guiana’s political circles working with Jean Galmot (taking over as Secretary General of the Parti de la Liberté following Galmot’s untimely demise) as well as the marriage of his daughter, Eugénie to Félix Eboué in 1922 serve to draw further attention to his chequered career as part of the bagne administration.